The Waddesdon Bequest at the British Museum Part 1 by Mark V Braimbridge

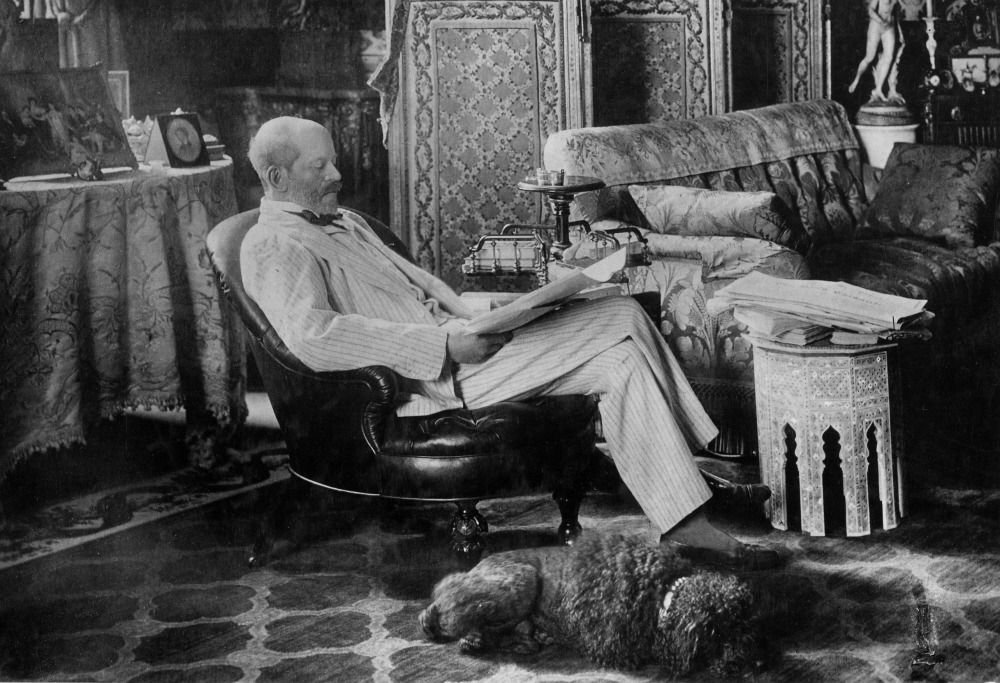

Baron Ferdinand Anselm de Rothschild (1839-1898)

The banking Rothschild brothers built mansions for themselves in the Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire countryside of 19th century England. Baron Ferdinand Anselm de Rothschild (fig 1) was brought up in Vienna and built his mansion, Waddesdon Manor, in the French Renaissance style in the village of Waddesdon just outside the County town of Aylesbury (fig.2). He married Evelina, an English Rothschild and his first cousin, who tragically died in childbirth 18 months later.

He then threw himself, aided by his sister, Alice, into collecting a wide variety of objects – French royal furniture, Savonnerie carpets, Sèvres porcelain, old masters’ paintings and art objects. These last consisted of 300 precious objects – painted enamels, ceramics, glass, masterpieces of goldsmiths’ work – and 21 intricately carved, miniature boxwood pieces, which he kept in the ‘new smoking room’ in the ‘Bachelor’s wing’ at Waddesdon Manor. He bequeathed the collection to the British Museum, of which he was a Trustee, in 1898, on condition that it was housed in its own separate designated room (now Room 45).

Rosary Bead

The word, ‘rosary’ is derived from the Latin rosarium, meaning a ‘garland of roses’ or ‘rose garden’, and denotes a set of prayer beads or the devotional prayer itself. A rosary provides a physical method of keeping track of the number of prayers said and is used in many religions for this purpose and also for meditation and even to relieve stress. A rosary bead (also called prayer nut or paternoster bead) can be made of precious stones – turquoise was thought by Native Americans to protect them in battle – wood, stone, plastic etc. The number of beads varies with different religions from 27 – 111 in Buddhism, 99 in Islam and is commonly 54 in Christianity with 5 larger beads marking the sequences of prayers.

This boxwood rosary bead is only 2 5/8 inches (6.7cm) in diameter, decorated on the outside with Gothic tracery and flower-heads (fig. 1).

It opens into two halves with the upper one closed by two doors (fig.2). On the outside of the left door is carved in low relief the Virgin in the Temple and, on the right door, the Marriage of the Virgin. On the inside of the left door is Moses and the Brazen Serpent and on the right the Descent from the Cross. On the inside of the upper half of the bead in deep relief is a minute carving of the Crucifixion with a crowded foreground under a vaulted roof, staged on several levels (fig.3).

The lower half of the bead is shut with a hinged flap (fig.2), which is carved on the front with the Annunciation, with the words spoken by the Virgin and the angel Gabriel as scrolls. On the back of the flap, which telescopes open, is the Nativity with smaller scenes of the Circumcision, Presentation in the Temple and Christ among the Doctors. Inside the lower half in deep relief is the Bearing of the Cross (fig 4).

The bead can be suspended from the rosary by a boxwood ring (fig.1)

Acknowledgements

My grateful thanks are due to Dr. Dora Thornton, Curator of the Waddesdon Bequest at the British Museum, and to Isabel Assaly of the Photographic Department, without whom this vignette could not have been written.

Photographs © The Trustees of the British Museum

Boxwood Medallions in the Waddesdon Bequest

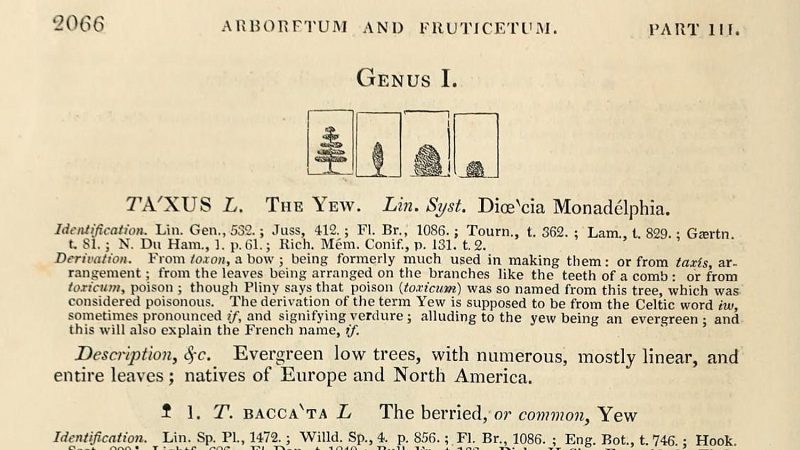

The invention of medallions is attributed to Antonio Pisanello, the Renaissance painter, who was better known during his lifetime for his medallions than his paintings and frescoes at the courts of Mantua and Verona in Italy in the 1430s and 1440s. A medallion is often a circular piece of metal, usually large, carved or engraved and worn as a fashion accessory on a necklace. These Waddesdon Bequest medallions are however of boxwood and were probably framed, as in fig. 1, in order to make them capable of being attached to a necklace. They were used or worn by the princes and wealthy merchants of Germany and illustrate the wealth and luxury enjoyed by such towns as Nürnberg and Augsburg in the 16th century.

Goedart Van Der Wier

Elderly Woman

Sibylla Duchess of Cleves

Maria, wife of Maximillian II

These four medallions are representative of the eight boxwood medallions in the Waddesdon Bequest in the British Museum. They illustrate the intricate carving of the artists of the 16th century in Germany and are a reminder of the adventurous lives led by the aristocracy of that century.

Photographs © The Trustees of the British Museum

This article was first published in Topiarius Vol. 14 Summer 2010 p15-17