Taxus for Topiary

Architectural & Landscape Historian Dr John Glenn, takes a scholarly look at references in English literature through the centuries, to the use of Taxus for topiary.

In 1906, the arboriculturist John Henry Elwes (1846-1922) stated ‘No tree, except perhaps the oak, has a larger literature in English than the yew’ (Elwes & Henry, The Trees of Great Britain and Ireland, (Edinburgh, 1906- 1913), Volume 1, P.120). Whilst there is some truth in this statement, the only book written exclusively about Taxus in the nineteenth-century, had been published just nine years before. Sir Joseph Hooker (1817-1911), the President of the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS), had actively encouraged the work and supported the publication of The Yew Trees of Great Britain and Ireland, (London, 1897) (Letter from John Lowe, 4, Gloucester Place, Portman Square.W., addressed to Sir William Hooker, dated 21st of June 1897, author’s collection). It was researched and written by a medical practitioner and amateur dendrologist, John Lowe (1830-1902).

As one would expect from a work endorsed by the President of the RHS, it is a work of horticultural and botanical merit. It also possesses a high level of antiquarian interest, as it includes chapters on the history of archery, druidical customs and poetical allusions found in English literature. Despite this antiquarian aspect of the book, it contains very little about the history of its use in gardens. Also an examination of these brief references indicate Lowe had a distinct bias in favour the ‘natural’ school of gardening as opposed to the formal and architectural. He was on friendly terms with William Robinson (1838-1935) and it is obvious that he shared the latter’s views on the iniquity of clipping Taxus, other than for its use as garden hedging. Biased or not, it is still a well-written and interesting book and a century later it is still regarded by many modern commentators as the standard work on the subject and it is still regularly quoted.

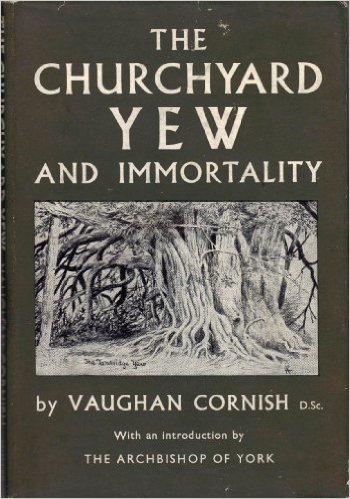

Over the next fifty years, only a lengthy article and a short monograph appeared. The first, published in 1926, is ‘Taxaceae at Aldenham and Kew’ by Vicary Gibbs (1853-1932) (Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society, vol. LI, (London, 1926), pps. 189 – 224) gives a detailed description of the large and varied collections of Taxus that were grown by or known at first hand by the author. Whilst there is some historical content, the value of this work rests almost entirely in its detailed contemporary account of one individual gardener’s experience of collecting and growing Taxus in many of its varied forms. The other significant work, albeit covering a different aspect of the subject, is ‘The Churchyard Yew and Immortality’ (1946) by Vaughan Cornish (1862-1848). The latter is a scholarly, but by no means comprehensive work that describes a postwar survey of ancient Taxus growing in Christian churchyards, primarily in England and Wales. Whilst articles continued to be published in popular journals, it was nearly half a century before another monograph devoted to Taxus appeared (Trevor Baxter, The Eternal Yew, (Worcs, 1992)). During the last decade of the twentieth-century several other books have followed. Their publication coincided with an associated ‘end of the millennium project’. Its commendable aim was to encourage the planting of at least one T. baccata in every parish throughout the United Kingdom.

In this age of media hype, the television botanist David Bellamy was at the forefront of this campaign. As a straightforward exercise in arboriculture little or no criticism could be levelled against it, but the campaign has spawned a much darker side. As a result a substantial percentage of the published work that has appeared in the 1990’s deals with the magical and mythological properties of Taxus. An extreme example of this is The Sacred Yew: Rediscovering the Tree of Life through the Work of Allen Meridith (1994). This is an extraordinary book, which ‘is primarily about a sacred tree.’ (Anand Chetan and Diana Brueton, The Sacred Yew (London, 1994), p. 12). Its main theme is to promulgate the fanciful ideology that Taxus is the guardian of the well being of the planet and as such the species is the most important living thing on earth. Claims of an equally surprising nature appear in other sections of the book. For example, amongst the methods described in the book for calculating the ages of ancient Taxus one is particularly bizarre. It is based on ‘the visions, dreams and psychic intuition of one very remark able man’ (Ibid, p. 3) Allen Meridith receives visitations from hooded figures in his sleep that enables him to assign ages of thousands of years to individual specimens of T. baccata. From an historical and archaeological perspective the peddling of such theories and practices is most unhelpful and merely serves to undermine the credibility of any serious scholarship on the subject. This is an especially serious point as the authors state that Meridith has convinced mainstream scientific opinion of the value and accuracy of his claims (Ibid, p. 8). There are two other works on Taxus, which were also published in the 1990’s. Hal Hartzell, The Yew Tree, a Thousand Whispers, (Oregon 1991) and Robert Bevan-Jones, The Ancient Yew (Macclesfield, 2002). Although the contents of the other two works are somewhat less fantastical than Chetan and Brueton’s propositions, all three concentrate on ancient specimens and none of them attempts to provide anything approaching a detailed history of the ornamental use of Taxus in English gardens.

In this age of media hype, the television botanist David Bellamy was at the forefront of this campaign. As a straightforward exercise in arboriculture little or no criticism could be levelled against it, but the campaign has spawned a much darker side. As a result a substantial percentage of the published work that has appeared in the 1990’s deals with the magical and mythological properties of Taxus. An extreme example of this is The Sacred Yew: Rediscovering the Tree of Life through the Work of Allen Meridith (1994). This is an extraordinary book, which ‘is primarily about a sacred tree.’ (Anand Chetan and Diana Brueton, The Sacred Yew (London, 1994), p. 12). Its main theme is to promulgate the fanciful ideology that Taxus is the guardian of the well being of the planet and as such the species is the most important living thing on earth. Claims of an equally surprising nature appear in other sections of the book. For example, amongst the methods described in the book for calculating the ages of ancient Taxus one is particularly bizarre. It is based on ‘the visions, dreams and psychic intuition of one very remark able man’ (Ibid, p. 3) Allen Meridith receives visitations from hooded figures in his sleep that enables him to assign ages of thousands of years to individual specimens of T. baccata. From an historical and archaeological perspective the peddling of such theories and practices is most unhelpful and merely serves to undermine the credibility of any serious scholarship on the subject. This is an especially serious point as the authors state that Meridith has convinced mainstream scientific opinion of the value and accuracy of his claims (Ibid, p. 8). There are two other works on Taxus, which were also published in the 1990’s. Hal Hartzell, The Yew Tree, a Thousand Whispers, (Oregon 1991) and Robert Bevan-Jones, The Ancient Yew (Macclesfield, 2002). Although the contents of the other two works are somewhat less fantastical than Chetan and Brueton’s propositions, all three concentrate on ancient specimens and none of them attempts to provide anything approaching a detailed history of the ornamental use of Taxus in English gardens.

In 1979, Richard Neil Melzack submitted a PhD thesis to The University of Hull, entitled ‘Some Aspects of Variation in Taxus baccata L. in England’. This is a botanical study, which examines the variations in leaf and growth form, which occur in three stands of mature trees that are growing in varying locations in England. The thesis is narrowly focused and does not make any claim to cover the history of the ornamental use of T. baccata in anything other than the most perfunctory way. The little history that is included in the text contains inaccuracies of fact and the author has not used any primary material (Richard Neil Melzack, ‘Some Aspects of Variation in Taxus baccata L. in England’, PhD Thesis for The University of Hull (December, 1979), pps). More surprisingly the variations of growth and form that are the stated core topic of the research are also very narrowly defined. For example the text does not include any of the many genetic aberrations, i.e. cultivars that are propagated for their ornamental value, such as the golden forms, that have become a feature in English gardens since the middle of the nineteenth-century.

For information on the introduction into England of the many cultivars, it is necessary to extract and collate the pieces of information that are found within the general body of literature referred to by Elwes, that appear in a diverse range of gardening and botanical books. Other sources that occasionally provide complementary information are topographical works and guidebooks. Much of the historical content of these articles can be disregarded as being merely repetitive plagiarism, but descriptions and observations of a contemporary nature can provide valuable clues which when added together can be used in the formulation of an understanding of the whole. It is necessary; therefore, to sift through a broad spectrum of contemporary texts in order to filter out the fragments that will help build up an accurate body of information.

Published references to Taxus are comparatively rare in the sixteenth and early seventeenth- centuries and these are confined in the main to works of a botanical nature, such as herbals. There are, however, scant references in books specifically on husbandry. This is some what surprising when considering the traditional role, promulgated by commentators from the nineteenth-century onwards, of T. baccata as a formal hedging and topiary plant in Elizabethan and Jacobean gardens. Henry states (1975) that during the first half of the sixteenth-century, very few herbals and gardening books were published in English, (Blanche Henry, British Botanical and Horticultural Literature before 1800, Vol. I, (Oxford, 1975), p. 71) and goes on further to argue that none of these were of any real scientific value being based in the main on ‘…ignorant medieval gardening beliefs.’ (Ibid, p. 57). The first English botanical book to be written in a truly scientific manner is The Names of Herbes by William Turner (c. 1508- 1658) (Ibid, p. 21). Whilst there is a small section on Taxus there are no references to its ornamental use. Turner merely states ‘The beste Vghe groweth in the Alpes… [and] Comune Vghe, groweth in diverse partes of Yorke shyre.’ (William Turner, Libellus de Re Herbaria, 1538: The Names of Herbes, 1548, Facsimiles printed by the Ray Society, (London 1965), p. 221). Apart from providing translations of the name of the tree in Greek, French and Dutch, it provides nothing else on the subject. This might be expected from a work intended primarily for apothecaries and physicians, but it is significant to find there is no mention of Taxus in The Gardener’s Labyrinth, (1594) by Thomas Hill (fl. 1540s- 1570s) (pps. 13-16). This begs the question, as to whether Hill as an oversight omitted it or because it was not commonly planted in the sixteenth-century English garden.

It is not until the publication of the first edition of John Evelyn’s enormously influential Sylva (1664) that detailed reference is made to the cultivation of Taxus as an ornamental plant. The book presents an extensive and wide-ranging catalogue of uses recommended by Evelyn for English parks and gardens. He also lists the many utilitarian items that can be made from its timber. Evelyn’s work ran into many editions over the next two hundred years, the author revised the first four and all were published in his lifetime. The fifth edition, published in 1729, is a reprint of the fourth edition, which reproduces the last revisions the author made to the text before his death in 1705. This final Evelyn version of the section on Taxus was reproduced without any alterations, in all four of the Alexander Hunter editions of the work, published between 1776 and 1812. Sylva maintained its popularity for over two hundred years and there are many examples of its use by different classes of English society. For example, Jeffrey Amherst (1717-1797) carried a copy of the third edition with him during his period commanding the British military expedition that conquered Canada (1758- 1760) (Author’s collection, Amherst’s signature is on the title page). Mary Russell Mitford (1787- 1885), the early nineteenth-century writer on country matters, taught the local vicar’s wife about the woods and trees surrounding their Berkshire village, ‘by the help of that delightful book, [explaining as it did] the differences of form and growth.’ (Mary Russell Mitford, Our Village: Sketches of Rural Character and Scenery, vol. II, New ed., (London 1829), pps. 111-112). Another arguably more famous nineteenth-century writer, Charles Dickens (1812-1870) also had a copy of the fifth edition (1729) in his library at Gadshill Place (Author’s collection, originally bought at the sale of the Gadshill Library, June, 1870).

The influence of Sylva was extensive and many English gardening books, published shortly afterwards relied heavily on Evelyn’s text. Some authors plagiarised sections of the text on the propagation of Taxus almost word for word. It is not until the early eighteenth-century, with the publication of foreign books on practical horticulture and garden design, translated into English that we find other authors giving their own practical instructions for the ornamental use of Taxus. These include three French works, Le Jardinier Solitaire by Francis.

Gentil (1706), The Retir’d Gard’ner (1706), translated by George London and Henry Wise and The Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712), translated by John James. All three books recommend, in a number of different ways, a formal use of Taxus, but as translations, they must predominantly reflect garden design in the French manner. A second, much enlarged edition of The Theory and Practice of Gardening was published in 1728, which was a straight translation of the French second edition, with no substantial English additions (F M G Cardew, ‘L.S.A.I.D.A., A riddle of Horticultural Authorship’, in vol. 74, The Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society, (London 1949) pps 256-261).

Once again the text recommends the formal use of Taxus. These translations were followed by the publication of original works written in English. For example, Ichnographia Rustica, by Stephen Switzer (1718), New Improvements of Planting and Gardening, both Philosophical and Practical (1718), by Richard Bradley, and New Principles of Gardening (1728), by Batty Langley. These texts present a contemporary English view of the uses of Taxus in garden design, which is at times somewhat ambivalent, as is the advice given in the First Edition of Philip Miller’s The Gardener’s Dictionary (1731). Revisions and updates of this important and comprehensive text appeared at intervals throughout the eighteenth and into the first decade of the nineteenth centuries. The subtle changes of text contained within the many editions provide an insight into the gradual rejection of the formal use of Taxus that occurred in the first half of the eighteenth-century.

As well as gardening books and dictionaries, works of a purely botanical nature have also provided useful research material relevant to the topic. A number of such books appeared throughout the eighteenth-century, the most famous of which is Species Plantarum (1753), by Carl Linnaeus. Useful research material has also been found in less well known works written by British authors such as Colin Milne (A Botanical Dictionary or Elements of Systematic and Philosophical Botany, (London, 1778)), James Wheeler (The Botanist’s and Gard – ener’s New Dictionary; (London, 1763)), and James Donn (Hortus Cantabrigiensis, etc. (Cambridge 1796)). Nursery catalogues have also provided another source of information relating to the commercial availability of specific varieties of Taxus. Many of these are merely printed as single broadsheets, but there are a few others, which are equivalent to a small book in size and content. A very early example of the latter form was published in the 1730s, which lists plants for sale by Stephen Switzer (A Catalogue of Seeds, Fruit and Forest Trees, Shrubs, Flowers, etc. Sold by S. Switzer, (London, 1735)). Another notable example is the much more extensive trade catalogue of Dicksons & Co (Edinburgh 1794), which runs to one hundred and ninety two pages (Catalogue Evergreen Shrubs, Fruit and Forest Trees).

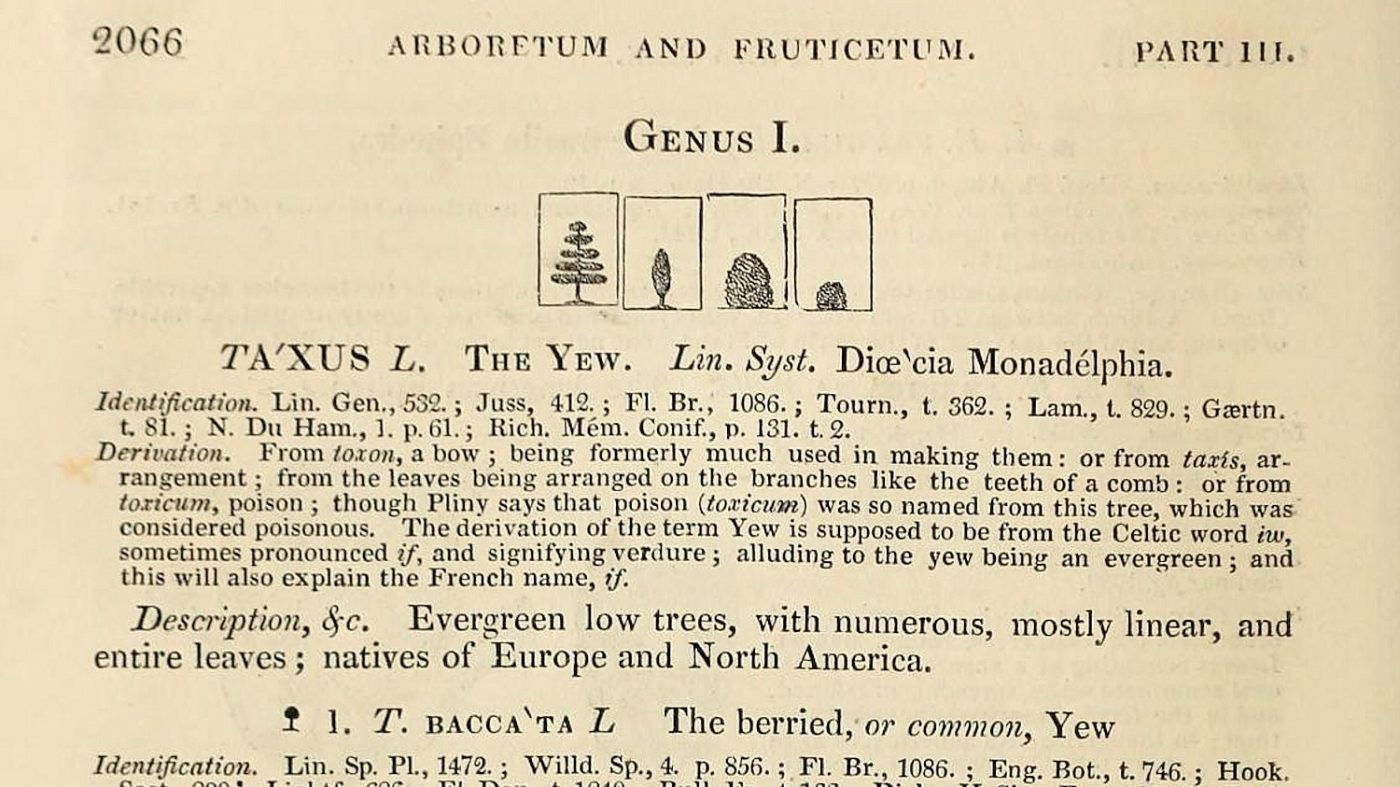

The proliferation of inexpensive books, together with the appearance in the late 1820’s of the first popular gardening journals, means that the nineteenth century publications provides historians with a very rich source of printed information on gardening and its allied design philosophies. A large number of J.C. Loudon’s works are of great value with Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum (1838) arguably being the most important, giving as it does an overview of contemporary knowledge about the species and cultivars of Taxus available at the date of publication. Loudon had been considering undertaking this monumental work as early as 1830, and by December 1834 approximately three thousand printed questionnaires had been sent out in an attempt to gather as much information as possible about hardy trees and shrubs grown throughout Britain. Due to his high reputation as a horticulturist, about sixteen-hundred replies were received, from dukes, marquises, earls and viscounts together with most of the leading horticulturists of the day (J.C. Loudon, Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum, vol. I, (London, 1838), p. xv). One hundred years after its publication it was still regarded by leading members of the Royal Horticultural Society as ‘one of the cornerstones of the horticultural library.’ (W. Roberts, ‘The Centenary of Loudon’s “Arboretum” ’, in Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society, vol. LXI, ed. By F.J.Chittenden, (London, 1936), p. 284). Nursery catalogues, which became more readily available after 1840, with the advent of the Penny Post, also provide a chronological source of information about the introduction of new varieties of Taxus. A very important early specialist catalogue is A Synopsis of the Coniferous Plants grown in Great Britain and sold by Perry and Knight at the Exotic Nursery, King’s Road, Chelsea (c. 1851). This work was issued as the first informative commercial catalogue of conifers available for purchase. It contains thirty-six species and cultivars of Taxus listed in the index. Seven years later, Gordon’s The Pinetum being a synopsis of all the Coniferous Plants at present known, with descriptions, History, and synonyms, and comprising nearly One Hundred New Kinds was published. This contains references to eighty-three Taxus species and cultivars, subsequent editions chart the available types of Taxus until 1880. Two other source works of importance date from the 1890’s: The RHS Conifer Conference published in 1894, and, as mentioned earlier, John Lowe’s monograph The Yew Trees of Great Britain and Ireland (1897).

Much of the body of literature referred to by Elwes is found in the gardening and antiquarian journals of the nineteenth century. For example, between its first introduction in 1841 and 1848, The Gardeners’ Chronicle and Agricultural Gazette included a total of twenty-four articles on Taxus (The Gardeners’ Chronicle and Agricultural Gazette, 1841 (two), 1843 (three), 1844 (nine), 1845 (three), 1846 (one), 1847 (one), and 1848 (five)). None of these cover the subject from the point of view of the use of Taxus as part of a designed garden. Between December 1849 and February 1850 however eleven articles by Robert Glendinning (1805-1862) were published in that journal. These were a continuous but serialised work, which described in great detail the amazing gardens that had been created during the previous fifteen years at Elvaston Castle in Derbyshire for the Fourth Earl of Harrington and his Countess. Of significance to this thesis, within this series of articles there are many descriptions and references to the remarkably extensive ornamental use on the site of T. baccata and more especially of its golden cultivars. The latter were then virtually unknown in English gardens and it is therefore truly remarkable that vast quantities were planted at Elvaston over a relatively short period of time. Glendinning’s articles on Elvaston created a great an interest in planting and developing these golden forms of T. baccata amongst gardeners and nurserymen. As a result, articles on the genus and its exotic varieties started to appear at regular intervals throughout the rest of the nineteenth-century. As well as The Gardeners’ Chronicle, regular examples can be found in other popular horticultural journals such as The Cottage Gardener, The Florist, Fruitist, and Garden Miscellany and William Robinson’s The Garden. Relevant research material was also extracted from The Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London (1812-1848) and The Journals of the Royal Horticultural Society (1860-1939).

As well as an increasing awareness of the design benefits to be derived from the ornamental planting of Taxus, the nineteenth-century also saw a growing public interest in the claims alleging many famous churchyard specimens were of enormous antiquity. A number of pseudo-scholarly commentaries on the subject are to be found in antiquarian, botanical and archaeological journals and some are also to be found in general books on trees, botany and gardening. Examples of the latter are works written or edited by writers such as Robert Mudie (1777-1842) (The Botanic Annual (London, 1832), p. 280), William Ablett (English Trees and Tree Planting, (London 1880), pps. 146-158), and Charles Alexander Johns (1811-1874) (Forest Trees of Britain, (London, 1854), pps. 341- 349). Much of this material also found its way into many of the inexpensive guidebooks that were being published in the latter half of the nineteenth-century. Vaughan states (1974) how ever that ‘The purchase of a guide may indicate a certain lack of sophistication in a reader.’ (John Vaughan, John, The English Guide Book c 1780-1870 an Illustrated History, (London, 1974)). A lot of these texts were aimed at the increasing numbers of amateur botanists, and antiquarians and, to be fair, the purchase of a guide also ‘points to a mind sufficiently alert to demand information and to a person with the leisure and economic power to satisfy this curiosity.’ (Ibid, p. 13). Articles on the great longevity achieved by specimens of T. baccata also appeared regularly in more general horticultural journals such as The Cottage Gardener (vol.XI (London 1853), pps 327-328). Many of these articles are often repetitious and sometimes downright contradictory.

Elwes was certainly correct about Taxus providing the nineteenth-century with the subject matter for so many articles. Into the next century the topic also continued to generate a lively level of literary interest. Many general works about gardening, botany and design principles, that were published throughout the twentieth century contain references to Taxus. Many of these modern authors have, however, unwittingly plagiarised erroneous text from earlier publications. As a result much that has appeared during the last quarter of the twentieth-century only serves to enforce the misinformation already in the historical and horticultural ‘chain of error’. The ‘invented history’ that this generates is a common thread through out the vast majority of twentieth-century works on Taxus is that few add anything significant or worthwhile to scholarship generally or to the subject of this thesis. Whilst this criticism often justifiably applies to the accuracy of the text of ‘Gardens Old and New’ found in Country Life Magazine (1897-1939) in many of the annual volumes there is a wealth of informative black and white illustrations of garden features made from living Taxus. Illustrations on the same theme can be found from the end of the seventeenth-century onwards, but these must always be treated with a degree of caution. From the middle of the nineteenth-century the advent of photography provides a further archaeological and historical resource but once again the images should be interpreted with care.

The article was originally published on page 50 of Topiarius Volume 17 Summer 2013 (additional links and images added for the web version of the article).

Special thanks to the Biodiversity Heritage Library & the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, McLean Library for the use of their material. Both websites contain a host of very useful research information from historic documents which are word searchable (the documents are also available via The Internet Archive).

![Portait of Henry Wise by Sir Godfrey Kneller [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.ebts.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Henry_Wise.jpg)

![Philip Miller By C F Maillet [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.ebts.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Philip-Miller-By-C-F-Maillet-Public-domain-via-Wikimedia-Commons.jpg)