Boxwood Engraving Blocks by Mark Braimbridge

Today wood engraving is flourishing again after a dismal patch in the 1960s and 70s when its simple black and white lines were thought to be dull and outdated. Like their predecessors, the new generation of engravers continue to work on boxwood whenever they could get it but it is in increasingly short supply. Lemonwood is the best substitute and is used by beginners to practise but it is inconsistent.

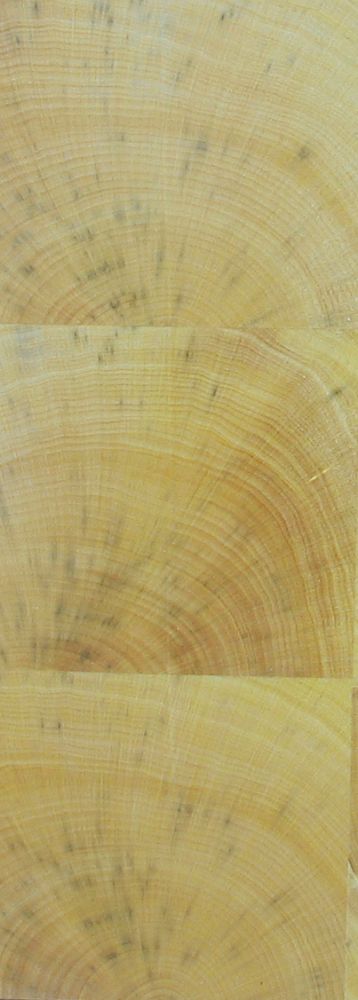

The ideal surface for a wood engraver has to be durable, of even hardness, absolutely smooth and light-coloured so that the engraved pattern can be seen through a prepared darkened surface – an irregular surface or consistency is anathema to an engraver. Only boxwood meets all these criteria.

Engravers work on boxwood in the form of “blocks” – thick, hand-made boards that can be fitted directly into a printing press. Each block is an assembly of one inch (2.5cm) blocks of boxwood, glued together with tongue-and-groove joins, with the engraving surface perfectly flat, polished by hand till it is as smooth as glass and a deep, glossy yellow The blocks vary from a few inches (cm) to a foot (30cm) in size.

Traditionally the two Buxus species used for block making were Buxus sempervirens and Buxus macowani from South Africa. South African supplies have dried up as have supplies of Buxus sempervirens from the Crimea and Turkey, leaving supplies from scanty British sources – the supplier is always on the look-out for boxwood trees being cut down. The wood is then cut at a sawmill into one inch (2.5cm) square slices and stored for some 3 years until it is fully dried as otherwise it tends to crack radially.

This article was originally published in Topiarius Volume 16 in 2012.

Reference

Uglow. J. (2006) Nature’s engraver: A Life of Thomas Bewick. Faber & Faber, London, pp 458

Acknowledgements

With grateful thanks to June Holmes of the Bewick Society, Carolyn Trew, the American Boxwood Society and Chris Daunt.