Boxwood in Classical Times – The Greeks by Mark V Braimbridge

Boxwood was a familiar wood in the Classical era of Greece and Rome and is not infrequently mentioned in their literature. It might be of interest to boxwood enthusiasts, as it was to the author, to explore more fully the contexts in which these quotations lie. Greek authors quoted by modern writers as mentioning the word boxwood are Homer and Theophrastus.

John Claudius Loudon [Loudon J.C. Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum 1838: 99; 1334] (1783 – 1843) was a landscape artist and encyclopedist, writing an ‘Encyclopaedia of Gardening’ and starting a vogue for ‘Gardenesque’, a style of formal garden design that had been out of fashion for a century. Many of the references in more recent boxwood literature are repetitions of Loudon’s important 1838 chapter on boxwood but neither he nor subsequent boxwood authors have given precise references for their quotations and it has therefore `not been easy to check their validity or their contexts.

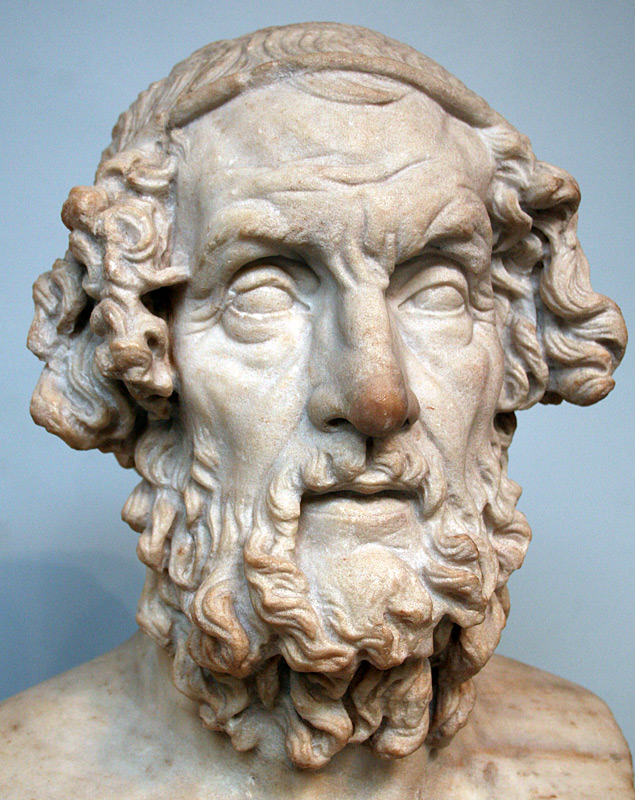

HOMER in the eighth century BCE wrote the Iliad, the epic poem of the siege of Troy by the Greeks, avenging the stealing of the beautiful Helen of Sparta by Paris. King Priam of Troy’s son, Hector, was the most prominent of the Trojan heroes and he killed in battle Patroclus, the close friend of Greek Achilles. In his anger Achilles stopped sulking in his tent, came out and killed Hector dragging his body round the camp, face down, dishonouring him and denying him the funerary rituals so important to both Trojans and Greeks.

Priam [Homer Iliad 24: 268] then went to Achilles with a mule-wagon laden with gifts in order to ransom Hector’s body and give it the proper burial rites:

“They (his sons) brought a strong mule-wagon, newly made, and set the body of the wagon fast on its bed. They took the mule-yoke from the peg on which it hung, a yoke of boxwood (ζυγὸν πύξινον) with a knob on the top of it and rungs for the reins to go through. This done, they brought from the store chamber the rich ransom which was to purchase the body of Hector.”

It was not all that rich a ransom but clearly the best that Priam could do after ten years of siege and it did contain useful clothing for the possibly ragged besieger, Achilles:

“Twelve cloaks of single fold, twelve rugs, twelve fair mantles and an equal number of shirts, ten talents of gold, two burnished tripods, four cauldrons and a very beautiful cup that the Thracians had given him.”

πύξος, translated into English script as ‘pyxos’, and into Latin as ‘buxus’, is of course the origin of our ‘boxwood’ (in America) and ‘box’ (in Britain).

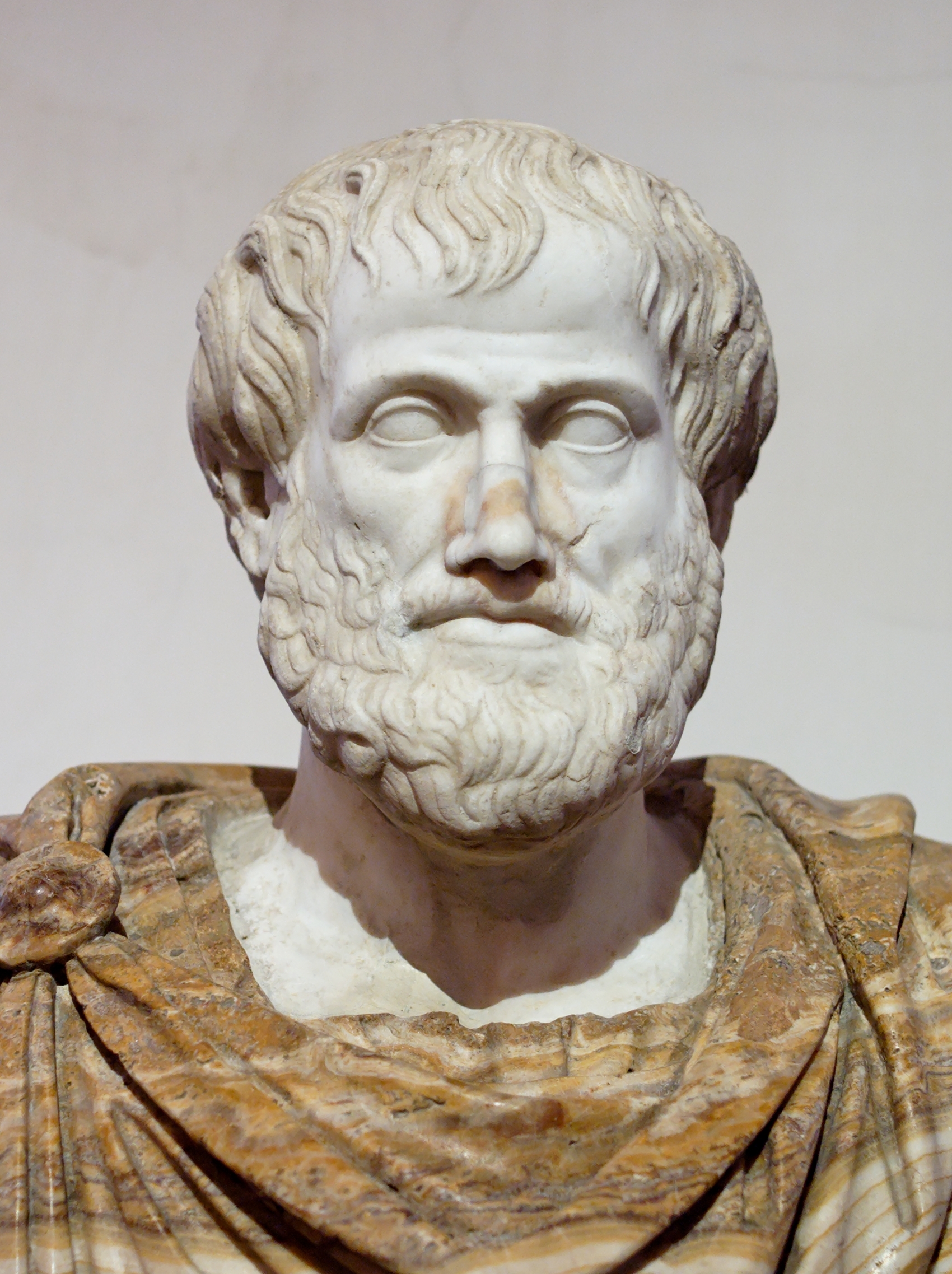

ARISTOLE (384 – 322 BCE), the Athenian philosopher and tutor of Alexander the Great, reported, in ‘On Marvellous Things Heard’:

“At Trapezus in Pontus honey from boxwood (πύξου μέλι) has a heavy scent; they say that healthy men go mad, but that epileptics are cured by it immediately.”

[Aristotle De Mirabilia 18 ]

A marvellous thing indeed! The medicinal uses of boxwood are surprisingly often, considering its poisonous propensities, mentioned in classical literature.

In ‘On the Universe’, his God, whose ‘motionless and harmonious rule’ guided the orderly arrangement of heaven and earth, created a selection of trees:

“For vines and date-palms and peach trees, and trees that bear no fruit but serve some other purpose, planes and pines and box trees (πύξοι).”

[ibid. De Mundo 6 ]

It is interesting to note how similar in concept in the fourth century BCE Aristotle’s God was to the Christian God. Also in his description of the legal system of Athens in the Athenian Constitution:

“Each juryman has one boxwood ticket (πινάκιον πύξινον) with his own name and that of his father on it.” to identify him. Important wooden articles were often of the hard, valuable boxwood at that time.

[ibid. Athenian Constitution 63: 4 ]

Aristotle was, surprisingly, not mentioned by Loudon.

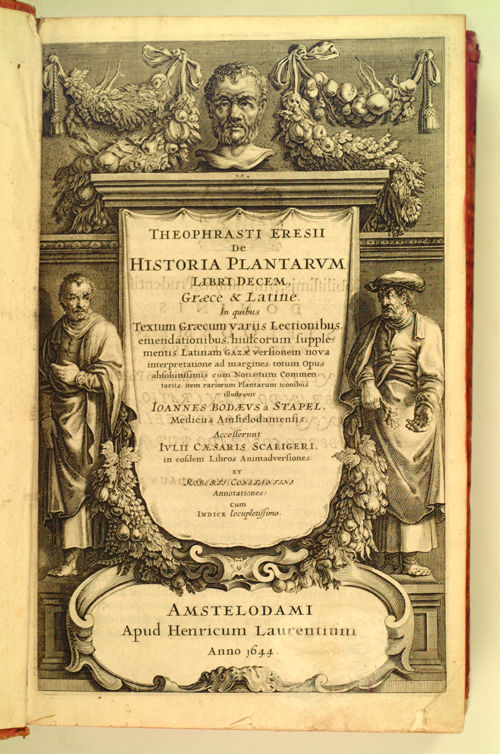

THEOPHRASTUS is quoted by Loudon:

“The box tree appears to have been first mentioned by Theophrastus, who ranks the wood with that of ebony on account of the closeness of its grain.”

[Loudon J.C. Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum 1838: 99; 1334]

Homer and Aristotle (above) had in fact previously mentioned boxwood and it has not proved possible to locate the Theophrastus ebony parallel – Loudon may have been confusing it with a similar quote by Pliny the Elder – so there is a case for amending this particular Loudon reference.

Theophrastus (371-289 BCE) was a philosopher of the Athenian Peripatetic school and was a favourite of Aristotle, becoming his successor at the Lyceum and inheriting Aristotle’s garden. His real name was Tyrtamus but Aristotle nicknamed him Theophrastus – ‘divine spoken’ – because of the grace of his conversation. He is called the ‘Father of Botany’, because, after the rediscovery of his works in 1483, he was the indispensable authority in the Middle Ages on the subject by virtue of his books on the history of plants, De Historia Plantarum, on the causes of plant growth, De CausisPlantarum, and his Calendar of Plants, in which he places boxwood on October 29th

In the Historia Plantarum he describes its growth characteristics:

“The box (Ἡ πύξος) is not a large tree, and it has a leaf like that of myrtle. It grows in cold, rough places; for of this character is Cytorus, where it is most abundant. It is largest and fairest in Corsica where the tree grows taller and stouter than anywhere else, wherefore the honey there is not sweet, as it smells of the box (ὄζον τῆς πύξου).”

[Theophrastus De Historia Plantarum 3: 15; 5]

It would be interesting to know if it still does today! But the depletion of native B.sempervirens in Europe makes it unlikely.

Πύξος (pyxos), somewhat surprisingly with its masculine –os ending, was feminine, e.g.Ἡ πύξος·, as Buxus is today.

CYTORUS (Κύτωρος). was a town in Paphlagonia in Turkey on the Black Sea coast. Cytorus is often mentioned as synonymous with boxwood as the mountains behind it between it and Amastris to the west were covered with the trees, clearly B.sempervirens from that particular area, as Turkish boxwood was the main source of European boxwood for centuries.

Other Greek authors mention Cytorus. Eustathius 7(300 – 377 CE) the Archbishop of Thessalonika in Northern Greece, quoted the Greek equivalent of ‘carry coals to Newcastle’ as ‘carry boxwood to Cytorus (πύξον εἰs Κύτωρον ἤγαγες).’

Strabo mentions Cytorus when describing his travels in Greek and Roman countries:

“The most and the best boxwood (ἀρίστη πύξος) grows in the territory of Amastris, and particularly around Cytorus.”

[Strabo Geographia 15: 1; 58]

NICANDER of Colophon (197 – 130 BCE) was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist and agriculturist. The colour of boxwood was frequently used in ancient times to describe pallor and yellowness. Describing herbal remedies, and in particular the Birthwort (Aristolochia clematitis), believed to be helpful in childbirth to induce labour, he said:

“The root of the male in colour resembles the boxwood of Oricus (πύξου Ὀρικίοιο).”

[Nicander: The Poems and Poetical Fragments ed. Gow ASF, Scholfield AF. Cambridge University Press 1953: Theriaka 516]

‘Oricus’ is thought by some to be the Val d’Orcia in Tuscany but is more likely to be the port of Oricus in Illyria (modern Albania). Birthwort was in this quote recommended as an antidote for viper bites.

And in describing the poison of toads:

“Whereas the voiceless one that frequents the reeds sometimes diffuses the yellowness of boxwood (πύξοιο χλόον) over the limbs, and sometimes bedews the mouth with a flow of bile.”

[ibid. Alexipharmaka 579]

STRABO (63BCE – 24CE) – Strabo was a name given to people who squinted – was a Greek historian and geographer. Apart from the Cytorus mention above, he quoted the philosopher, Megasthenes, as saying that:

“The ivy, laurel, myrtle, box-tree (πύξοι), and other evergreens, no one of which is found on the far side of the Euphrates except a few in parks, which can be kept alive only with great care.”

[Strabo Geographia 12: 3; 10]

It is still not easy today to grow boxwood in that part of the Middle East. The paradises of the Persian satraps had nothing to do with gardens: they were enclosed parks for the preservation of game [A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities eds. Smith W., Wayte W., Marindin G.E. John Murray, London 1890].

LUCIAN (125-180CE) was a rhetorician, pleading cases in court. He wrote solely, he said, ‘to amuse’ and he has been called the ‘Father of Science Fiction’, because he wrote about extraterrestrial travel.

Pyxion (πύξίον) was a tablet of boxwood covered in wax and was a common writing material before the advent of paper, which was not invented in China until 105 CE and did not reach Europe until the 8th century. In his ‘Ignorant Bookkeeper’ [Lucian Adversus Indoctum 15] Lucian wrote of Dionysios producing poor tragedies in the annual Athenian drama competitions, which made him procure the wax tablets that Aeschylus used (Αἰσχύλου πύξίον) to improve his results. With no success! Pyxion later became synonymous with a waxed tablet made of any wood.

Pyxis (πύξις) was a small box or casket, which was usually made of boxwood because of the wood’s suitability for carving small articles. Some believe that this resulted in the giving of the name pyxos (πύξος) – and in Latin buxus – to the wood from which it was made. Lucian [ibid. Asinus 12] persuaded a maid to let him watch through a crack in the door her mistress stripping naked, opening a large box containing numerous small ones (πολλὰς πυξίδας) and anointing herself with the contents in order to turn herself into a bird! A voyeur’s excuse perhaps?

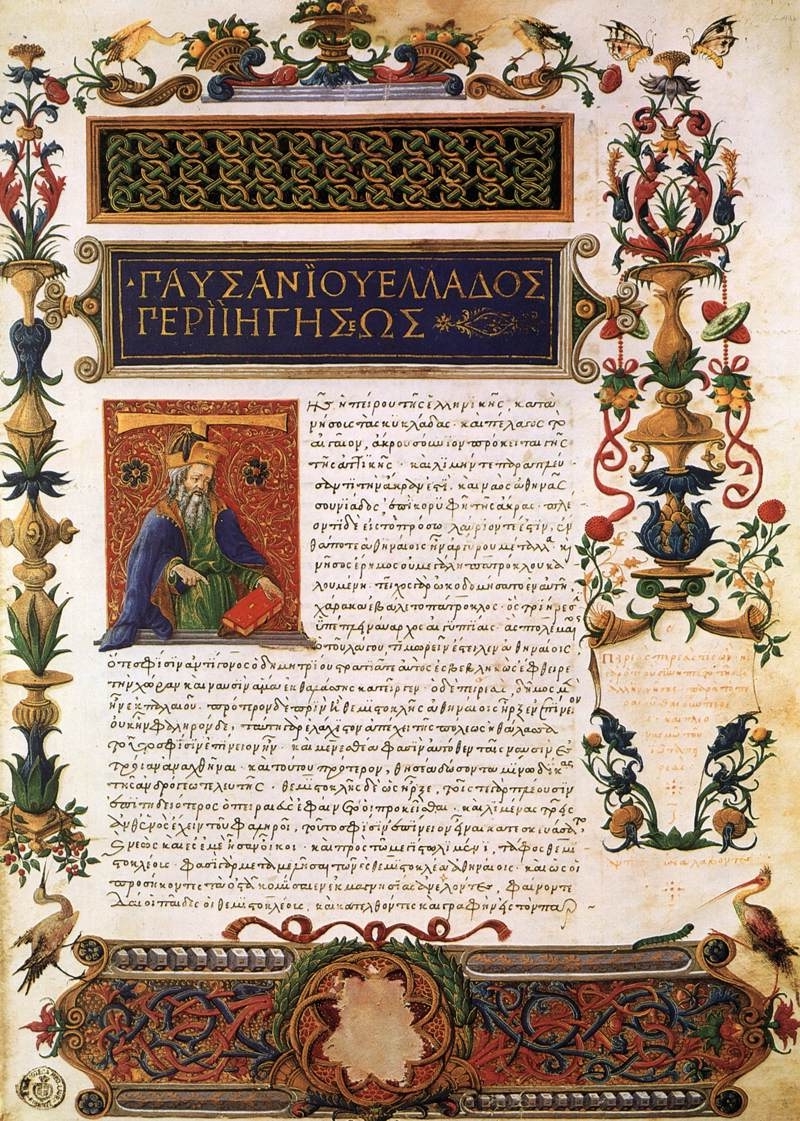

PAUSANIAS (115 – 180 CE) was a doctor from Greek Asia Minor who travelled all over Greece for 20-30 years in around 160 CE describing the country. He was particularly interested in religious art and architecture. At one of the treasuries in Olympia, the site of the first Olympic Games which started as a small local festival there in 776 BCE, he noted the statues and ceremonial shields:

“There stands a boxwood image of Apollo with its head plated in gold (ἂγαλμα πύξινον Ἀπόλλωνος)”

[Pausanias Description of Greece: Elis II. 6:19; 6]

The image was sculpted by Patrocles. Boxwood was considered suitable for carving important and valuable objects then as later.

In conclusion, boxwood (πύξος) appeared in Greek literature as wood for fashioning hard, tough and long lasting articles by Homer, Aristotle and Pausanias. Its pale colour made it used as a metaphor for pallor by Nicander. Theophrastus and Strabo mention its geographical distribution and its cultivation problems in dry climates. Its characteristic smell, liked by some, disliked by others, is noted by Aristotle and Theophrastus, with small boxwood caskets and waxed boxwood writing tablets quoted by Lucian.

There is little in the literature describing Greek gardens. The Greeks evidently had little taste for landscape beauty, with plants mentioned primarily for their practical or commercial properties [A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities eds. Smith W., Wayte W., Marindin G.E. John Murray, London 1890]. Still it is easy to exaggerate their utilitarian tendencies: if the supply of plants was regulated by commercial principles, the demand itself testified to the love of them for their own sake.

The Greeks then were familiar with boxwood wood but almost certainly not with its horticultural possibilities.

Acknowledgements

My thanks are due to the staff of the British Library, the British Museum and the Institute of Classical Studies Library of London University. Particularly grateful thanks are due to my classmate, Christine Rennie, without whose skilled scanning of classical literature this article could not have been written.

This article was from The Boxwood Bulletin of the American Boxwood Society and appeared in Topiarius Vol.11 – Summer 2007 pages 11-13